Originally written for: Runtastic’s tech blog

HOW DOES IT BEGIN?

Usually, on boarding in a new job passes in a slow rhythm during the first couple of months. That was the case with me at least, getting to know how our infrastructure at Runtastic is built, how the services interact with each other, how to monitor services you are responsible for, reading the guidelines, etc.

Shortly after I joined, I got to build a prototype with one of my new teammates. We were on track, and we got to monitor a release of a new service within our team’s responsibilities; we got a quick training on how to monitor the release and what numbers we need to look at. We knew what to do, as the knowledge transferred a couple of days before the release, and everything was good to go.

And technically speaking, the release performed well internally and for some trusted users a couple of weeks before the shout out and telling the public, so no problems were expected.

The morning of the release was fun. I had just arrived at my desk and my colleague said, “The workers are down.”

THE FIRST TALE: KNOW YOUR LIMITS

We run our microservices with jRuby. It’s efficient, and we have real threading. We also use Sidekiq with Redis for running background jobs. I tell you this, because it’s important to know the potential impact of the stack you use.

Basically, we had increasing numbers of the dead jobs set in our workers servers.

We also have an automatic mechanism to shut down the workers if the dead set reached specific limits; Sidekiq has a (default) limit of 10,000 jobs which can be stored as dead jobs. A dead job is a job that exceeds its retry limit and is not configured to skip the dead jobs queue.

When reaching the limit, jobs are lost, hence the mechanism:

sidekiq_retries_exhausted do |msg|

if Sidekiq::DeadSet.new.size > (Sidekiq.options[:dead_max_jobs] - DEAD_JOBS_THRESHOLD)

Sidekiq::CLI.instance.launcher.quiet

end

end

And we ended up with a non-working service with a dead set full of jobs with “too many open files” errors.

For that error to show up, you could have hit the limit imposed by your OS for the file descriptors, or maybe the limit itself is a bit low during your server provisioning phase. Also the process of your web server could be behaving weirdly.

ulimit -a is a *nix tool, which could help you identify most of the resources’ limits in your box.

We need the file descriptor one – ulimit -n– which gives you the limit of open files in your machine.

It turned out we have a high number of open files across all of the processes. We also used lsof to see how many files our server process opens:

lsof | awk '{ print $2; }' | uniq -c | sort -rn | head

I will let you find out what this command does as homework – feel free to leave a comment about it.

As the number of open files was really high, we were looking into the file manipulation we do in our service more closely:

You can use File.open in ruby in two ways: with a block or without it.

File.open('foo', 'w') do |file|

# Do stuff with file

file.write "bar"

end

file = File.open('foo', 'w')

# Do stuff with file

file.write "bar"

file.close

It turned out we used the latter, where we should close the file after reading it ourselves. We closed the file, but if an exception happens before we close the file, it will remain open.

So we added an ensure clause:

def method

file = File.open(foo, 'w+')

# Processing and stuff

ensure

file.close

end

After patching and closing the files properly and communicating with the OPS team to increase the limits in our servers, the issue came back the next day.

At this point, we revised most of the code we open files in and tried to see what’s wrong there, but we found nothing.

IT’S ALWAYS IN THE LOGS

A temporary fix was to monitor when we reach the file limits and restart the process. This worked until we figured out the issue.

The next morning I opened New Relic and tried to trace the error one more time. Hidden between the stack trace there was a line from a third party library.

We used an unofficial gem (shareable libraries are called “gems” in the ruby world) to manipulate vendor specific XML files, because the official SDK for working with these XML files was written in Java.

It turned out that the unofficial gem opened the files, did some processing, and closed the files, but again, if something failed in between, it would remain open.

I patched a fork of the gem and deployed it and also pointed out this issue to the maintainer so he could fix it.

The open files error didn’t show up as quickly as before. Thankfully my teammate focused on speeding up finalization of the gem we are building (a ruby wrapper around the official SDK) and we had it done quickly. We replaced the old gem with it, and we have never been happier.

THE SECOND TALE, WHERE’S MY DATA?

One day someone approached our desks and said, “I noticed something weird, I did some running sessions yesterday and tracked it with my smartwatch, but some sessions were missing.”

This was related somehow with the release we did, the service basically worked as an importer for the XML files from the watches and supported hardware into our system. So when you have a sports session, you could find it under your Runtastic account, if you connected them, of course.

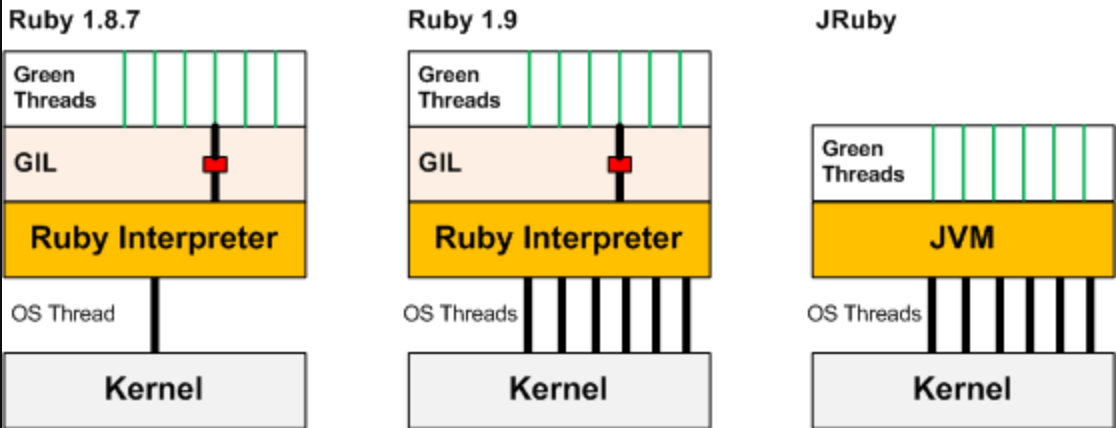

I consider myself a Rubyist; I use ruby as my main language because I love it, I read about “_why the lucky stiff” and knew lots of what was in the community even before becoming part of it. I know that ruby has no real threads because of the GIL thingy. Before even starting using the language, I never had to worry about the threading issue before and was happy using MRI anyway, but now this haunted me.

From the figure above, you get a general overview of how jRuby has a real threading model. So if you use jRuby, you need to make sure your code is thread-safe, otherwise you will have a pleasant time debugging weird errors.

jRuby by default ensures the standard libraries are thread-safe for you. After a bit of investigation, I found we silence_stream used from active_support, which is not thread-safe. I removed it. We also tried to revise most of the code to make sure we are not abusing memoization or += incrementers as most of these are not thread safe. The real issue is we don’t use threaded code, so this bug comes from a hidden place. Also reproducing a bug like this locally is really hard; as you know, thread-safe bugs are pain in the ass.

We went deeper to know where the places are which we could put shared data between threads and tried to do some tests for the new gem we built. Since it’s a wrapper around a Java SDK, which acts as a black box to us, we wanted to make sure the issue doesn’t come from there first.

COUNTDOWNLATCH AS A TESTING MECHANISM

One of our architects suggested using CountDownLatch for testing the gem thread-safeness.

The idea was simple: I start reading files inside a thread and before processing the files, I latch the thread. I do the same in a second thread. Then I countdown and let the threads race to process the files.

require "concurrent"

it "is a thread-safe" do

latch = Concurrent::CountDownLatch.new(1)

sample_1_records = nil

sample_2_records = nil

t1 = Thread.new do

file = nil

File.open("./spec/xml_samples/sample1.xml") do |f|

latch.wait

file = XmlDecoder::Reader.new(f.to_inputstream).read

end

sample_1_records = file.sessions.last.records

end

t2 = Thread.new do

file = nil

File.open("./spec/xml_samples/sample2.xml") do |f|

latch.wait

file = XmlDecoder::Reader.new(f.to_inputstream).read

end

sample_2_records = file.sessions.last.records

end

latch.count_down

t1.join

t2.join

expect(sample_1_records.size).to eq(2518)

expect(sample_1_records.last.altitude).to eq(2242.800048828125)

expect(sample_2_records.size).to eq(406)

expect(sample_2_records.last.cadence).to eq(76)

end

I got unstable results, which means the gem has a thread-safe bug. Looking quickly into the code we found that we used instance variables inside modules, which means they are module variables and shared between threads.

module XmlDecoder

def self.read(inputstream)

# Not so good.

@activity = Activity.new

end

end

module XmlDecoder

def self.read(inputstream)

activity = Activity.new

end

end

That went off our radars, so we quickly bumped the gem and deployed it. And we are back to being happy again**.**

THE THIRD TALE, PATCHING PRODUCTION CODE, OR HOW I STOPPED WORRYING AND LET IT GO

No matter what, production has its own rules. We always act like we don’t patch directly on production, always hot fixing code instead. We talk about best practices, reproduce it locally first. We shun those who say they don’t actually follow the rules, while in critical situations, you really need to act quickly and sometimes stop the bleeding first before it can heal.

One day, we merged a Pull Request and deployed it to production, but all of our servers couldn’t get up. Workers were down, servers were down. It was weird that the PR and tests passed the CI and most of the environments, but failed on production, which should be no surprise within the wild and harsh land of production.

Getting into the server and trying to read the logs, the error was mentioning a model we’d never had a problem with before. I commented out a suspicious line within that file, restarted the server, and the process came up; The line was basically just re-defining an already defined dry-struct object. With dry-struct, if you initialize struct attributes, you can’t define it or alter it anymore. It’s immutable and this is why we use it.

Removing that line fixed the issue. For some reason, the error was tolerant in CI and testing environments and just showed the error in console, which for some reason got swallowed. Tests were passing, which just caused a fatal error in production.

Working with assumptions on production is a bad way to mitigate an issue, but in the wonderland of production you might compromise a little bit to get stuff working until the main fix lands. You need to stop the bleed before healing in a clean way.

You also need some luck; trust me.